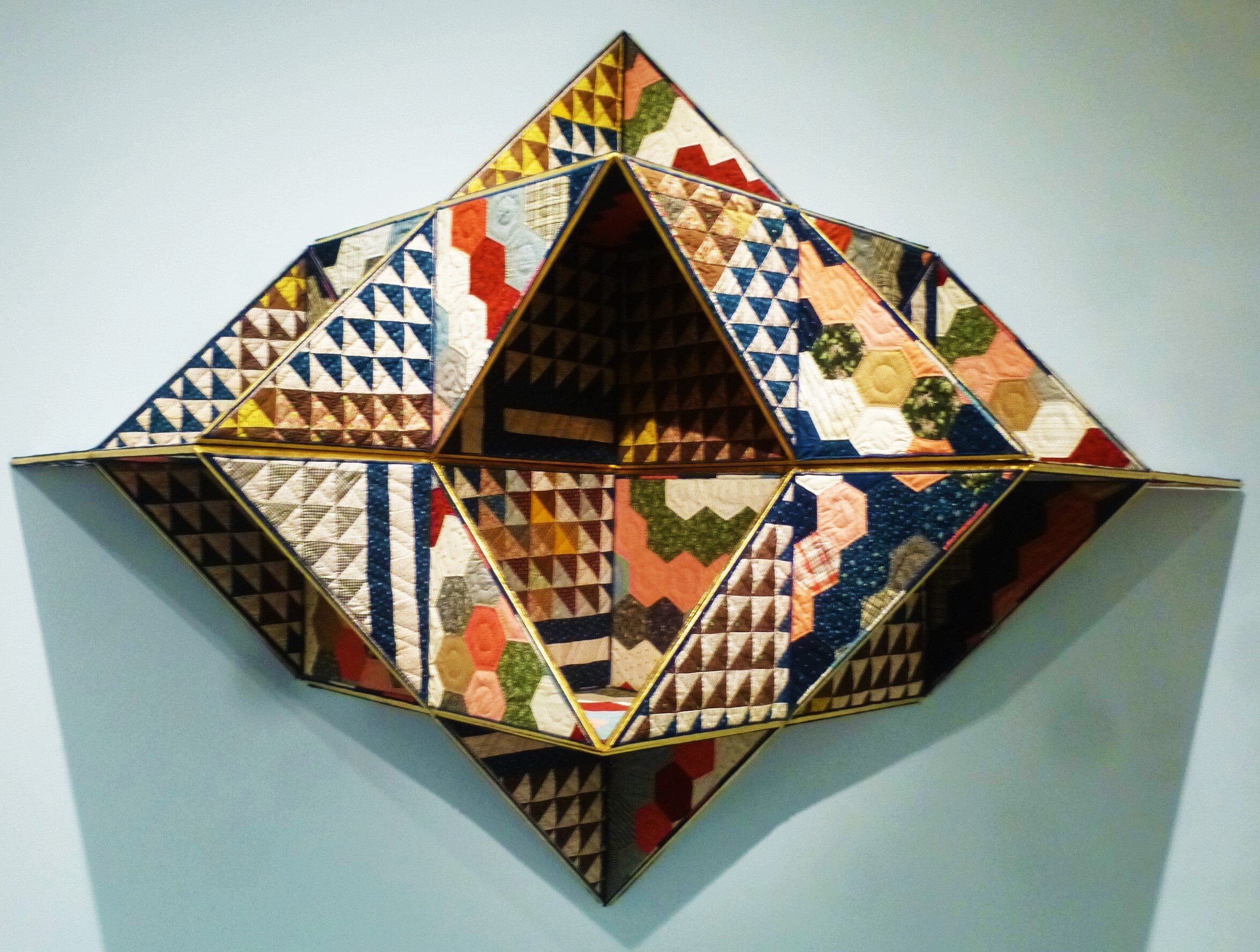

Kemestry by Sanford Biggers (Antique quilt, birch plywood, gold leaf).

The Dirty South: Baptism by Sight and Sound

by Charles McGuigan 06.2021

Total immersion is the best sort of baptism: every pore, every follicle, every pathway to your senses, caressed or assaulted, by water, by fire, or, in the case of the VMFA’s latest installation, by sight and by sound.

The Dirty South, curated by Valerie Cassel Oliver, cleanses the human soul, washing away denial and the sugar-coated White lies that have persisted in this country for over four centuries. And with this baptism comes a revelation about the very foundation of Southern culture, and, more broadly, American culture.

Just before you descend into the exhibition area, a slab—slow, low, and banging—greets you, foreshadowing what lies down below in the heart of it all. Born in Houston’s hip-culture back in the 1980s, slabs are Detroit classics with glossy paint jobs, plush interiors, mind-numbing sound systems, and of course swangas, also called Texan Wire Wheels. The Cadillac featured in this exhibition was customized by New Orleans-based producer and rapper Richard “Fiend” Jones, aka International Jones.

Crucifixion (Blue Jesus) by Mose Toller (Polychrome wood).

Once down the stairs, music engulfs you, along with visual stimulations. It seems almost labyrinthine, but you are led by an invisible thread of sound in the form of music and the human voice, as you begin a sonic and visual journey through the cultural history of the South, beginning a hundred years ago. You move from jazz to the blues to rhythm and blues to soul and finally to Southern hip hop, and the sounds are accompanied by more than 140 works of art that range from paintings to sculptures to drawings to photography to film to audio pieces and large-scale installation works.

When I enter one of the installations, I can feel the temperature rise by at least five degrees and the hairs on my arms stand up as if electrically charged.

The room pulses with a heaving red, almost womblike, lit by a single, naked incandescent bulb. Its walls and floor and ceiling are constructed of rectangular swatches of vinyl in varying hues— scarlet, vermillion, carmine, crimson—stitched together with black thread like an enormous patchwork quilt. Even the cross and lectern and pews are swaddled in red.

Within this space the air is much closer than it is in the rest of the exhibition area, and it begs you to absorb and linger and learn, which is probably as it should be, because this installation depicts a very famous chapel at Dockery Farms (Plantation), Mississippi. Out of its doors, a little over a century ago, spilled an endless stream of a new music from Charley Patton, Henry Sloan, Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Brown, Tommy Johnson, and Roebuck ‘Pop’ Staples, who had all belted out songs from their guts in this most sacred of places, giving birth to the Blues.

Over the course of my life I have seen hundreds of art exhibitions in museums across the country, but none possessed the raw, emotional and lasting power of The Dirty South. Different artists may inspire our aesthetic sensibilities, and it’s pleasant to wallow in them. The Dirty South does that with scores of artists, but it does much more: It is transformative. Those who enter will not be the same when they leave, and the metamorphosis that occurs is not merely emotional or intellectual. It is spiritual.

From Asterisks in Dockery, Rodney McMillian (Vinyl, thread, wood, paint, light bulb).

If you leave the final room of The Dirty South, having watched the video ‘Love is the Message/The Message is Death’ produced by Arthur Jafa, and still do not understand what Black Lives Matter means, you are soulless or witless or simply an ignorant white supremacist incapable of grappling with truth, content instead to regurgitate and swallow, again and again, the ludicrous pablum of the Southern myth called the “lost cause.” In a little over seven minutes, Jaffa invites us all to consider the Black body as a sort of “repository of history, tradition, and knowledge, as well as a site of trauma, resistance, and resilience.” Some of the images in this video, which runs a little over seven minutes, will force you to recall another video that ran a little over nine minutes. Shot last May on a cell phone by Darnella Frazier that video showed the sadistic murder of George Floyd, who died beneath the knee of a white police officer.

Every Southerner from Texas to Florida, from Georgia to Virginia, should see this creation. Every American should. And every child in every school needs to see this exhibit either in the flesh or remotely, for it is essential to understanding the stuff we are made of as a people. (On June 8, Governor Ralph Northam offered free admission to this exhibit for every child, pre-school through 12, and their immediate families.)

Along with the pain, the struggle, the joy and the resistance ensconced in the music and the visual art work, there is also an undeniable history lesson here, one that blows to smithereens all the idiotic tales of Southern history primers. This is the blemished truth about our Dirty South.

By the time I leave the museum with a friend, I am literally breathless. (I will visit the exhibit on three more occasions over the next two weeks, and each time the effect will be the same.) As she goes off to her car in the parking lot, I head out to Arthur Ashe Boulevard where I’m greeted by a truly heroic equestrian monument created by Kehinde Wiley that does more than symbolize a sea change in Southern culture.

Of The Deep South and its organizer, here’s what Connie Butler, chief curator at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, had to say: “What the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts is doing is radical. Valerie (Cassel Oliver) is spearheading really incredible efforts to make the city look at its history with slavery, and in that context, this exhibition is especially important.”

When I look up to Rumors of War, the rider—a young Black man with dreadlocks in a ponytail, wearing jeans ripped at the knees and Nike high-top sneakers—looks absolutely triumphant.

Exhibit runs through September 6

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

200 North Arthur Ashe Boulevard

Richmond, VA 23220